First 100 Days at CAIS

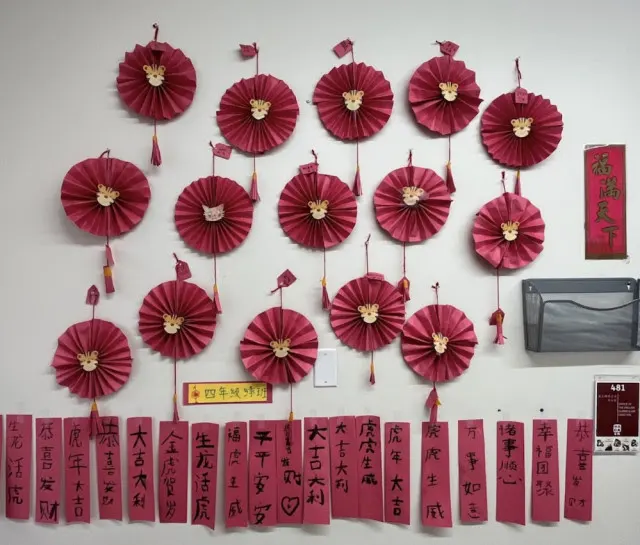

In light of celebrating the Lunar New Year in a huge way tomorrow, it means so much to me and my fellow Chinese faculty to see our beloved memories and traditions being honored in our school community this week, such as a school wide New Year lunch meal, cultural art activities, and most importantly, the uplifted spirit that every single person is grounded with at CAIS. As the Year of Tiger is opening a new door for us to move forward as a school, it is amazing for me to reflect how far we’ve come just in my first 100 days at CAIS. I have attached below a short video consisting of one-second clips that are a quick record of these 100 days at CAIS. Enjoy and “see” you tomorrow!

Wishes and Prospects for the Chinese Program

By Chinese Program Director Cindy Chiang

This year, the first day of the Lunar New Year falls on Tuesday, February 1, 2022. For those of you who did not grow up in Taiwan or China, you may find it hard to imagine how Chinese New Year is traditionally celebrated over the course of two full weeks, culminating in the Lantern Festival on the 15th lunar day. Growing up in Taiwan—where the entire island gets into a festive mood as early as a couple weeks prior to the first day of the new year—I have countless fond memories of celebrating this holiday as a culturally important occasion. Even for a land that is so small, numerous local and regional customs and traditions are diversely practiced and filled with magnificent Taiwanese kindness and hospitality. These traditions fall into five categories: Food (食 shí), Clothing (衣 yī), Home (住 zhù), Transportation (行 xíng), and Education & Recreation (育乐 yù lè).

Food – 食 shí

New Year’s Eve Reunion Dinner (年夜饭 nián yè fàn) is, no doubt, the highlight of this entire holiday. This is the time you can easily see so many cooks—typically all the wives in a family—preparing for this grand feast with a variety of dishes that hold a special significance and are chosen for luck, accompanied with a big hot pot in the middle of a round table.

Clothing – 衣 yī

It is almost a must for parents to buy some new clothes for their children. People want to have a fresh start walking into the new year and wearing something red has a symbolic meaning of bringing them fortune and good luck for the whole year.

Home – 住 zhùPrior to the holiday, House Cleaning (大扫除 dà sǎo chú) is another must. Cleaning out some unused and overstocked objects, sweeping dust out the door, and clearing dirt off the windows symbolizes that you are removing any bad luck accumulated from the past year (除旧布新 chú jiù bù xīn).

Transportation – 行 xíng

With everyone traveling to be with family for this holiday, I recall that this is the time of the year that the TV news has constant updates on the traffic status in Taiwan. They would promote the idea of carpool lanes for at least four passengers and the idea of using alternative transportation. The news would also show how the one and only highway that goes through the whole island (that all Taiwanese people rely on) was jam packed.

Education & Recreation – 育乐 yù lè

Setting off Firecrackers (放鞭炮 fàng biān pào) and Playing Mahjong (打麻将 dǎ má jiàng) all night long are the most representative ways that illustrate the cultural importance of family gatherings and bonding. On the first day of the new year, young kids will greet the elders with auspicious words and then receive Red Envelopes (红包 hóng bāo) that contain money as a way for the elders to give the young kids blessings.

Due to the current circumstance with COVID again for this holiday, many ethnically Chinese people acutely feel they have been away from home endlessly. This massive sense of longing for family reunion strikes me hard as somebody’s daughter, aunty, and cousin who is counting down days until we unite again. The sentiment and nostalgia for home is far beyond my words and I am allowing this feeling of wistful affection for all my family to flow through my mind and body as I am welcoming the Year of Tiger. (The tiger resonates with me as a Chinese Zodiac (十二生肖 shí ‘èr shēng xiào) sign that represents people who are courageous, active, and love a good challenge and adventure in life.)

That being said, the faculty, staff, and my wonderful administrative colleagues at CAIS and the mission for the Chinese program are like super glue firmly holding all the pieces of me together. In addition to the upcoming Lunar New Year, today I have another important occasion to celebrate—January 27 marks my 100th school day at CAIS as the Chinese Program Director!

Looking back at the past 100 days, I am pleased to report that our program, even in the face of pandemic challenges, keeps its eye on our Strategic Vision and Reimagining CAIS in a variety of ways. The discussions with our Chinese faculty members have been inspiring. We’re working to stimulate and challenge new perspectives on the way Chinese teaching and learning is traditionally viewed and implemented, particularly in the areas of building oral skills in a play-based setting, re-evaluating language assessment, aligning literacy curriculum, delivering instructional best practices, and fostering students’ agency and their innate curiosity about learning.

In addition to this goal-oriented work, we are investing a great amount of time in leveraging faculty leadership capacity, building relationships, and making connections with the whole community in different ways, whether classroom visits, participation, demonstration and substitution; Zoom meetings; faculty social gatherings; and on to the climax of preparing for the grand Mass Greeting that is taking place tomorrow! Beyond school, I have worked with a group of our Chinese faculty to submit proposals for the National Chinese Language Conference (NCLC) as well as the Early Childhood Chinese Immersion Forum (ECCIF) based on each individual’s expertise.

Every single one of these 100 days has been so abundant and fulfilling that it makes my fondness for CAIS fill my heart and help balance the nostalgic yearning towards my family in Taiwan.

Last but not least, here’s wishing you a wonderful Year of the Tiger and continued success, growth and prospects in CAIS’s Chinese program.

祝大家虎年心想事成 , 健康平安

Cindy Chiang

Chinese Program Director

Jeff’s New Year’s Greeting

“Support Recycling” (aka Greatest Hits Series)

By Head of School Jeff Bissell

As we inch toward the Year of the Tiger, I have been laboring to get my head out of the Omicron space and more into the festive Lunar New Year spirit. For inspiration, I looked at everything I’d written about LNY since my first year at CAIS, 2010-2011, when only a few of you were here. Here is the very first thing I ever wrote to the CAIS community about the New Year, which to me has stood the test of time. I hope you’ll enjoy it!

In mainland China, where I lived from 1999 to 2010, school children enjoy a month-long lunar New Year holiday. Because I worked in a school during those years, I always traveled during that time. I lived in Beijing, which was home to millions of rural migrant laborers, and each year when the New Year rolled around, the migrants headed out of town—they were going home to spend the holidays with their families in small villages all over the country. I usually headed to either Yunnan or Guizhou, both mountainous provinces in the southwest, where I too would spend time in villages that bustled with the excitement of sons and daughters returned home for the holidays. In the villages, envious residents listened to the urban tales of their returned neighbors who had left their homes to work on construction sites, in restaurants and in factories in cities like Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou and Dongguan, earning the equivalent of $100, $150 even $200 a month—an unimaginable amount for farmers in the mountainous villages of southwest China. I knew that in the big cities of China these migrant laborers were members of an underclass, looked down upon by their urban countrymen who drove Toyotas, Volkswagens, or even Audis and lived in three bedroom, heated apartments. It is estimated that some 150 million rural Chinese have left their villages and moved to cities in search of work—the biggest mass movement of human beings in history. These people have fueled China’s double digit economic growth rates for the last 30 years. And every year, as the lunar New Year approaches, millions and millions of them cram into trains and buses, leave their city jobs behind, and journey back home—the only chance they will have all year long to see their family members and friends. Every year the villages have more TVs, more motorcycles and more karaoke machines than the year before—all paid for with money sent back by family members laboring in China’s cities. Many people told me that the biggest source of cash income in the villages I visited was family members who had migrated to cities, found work, and sent their earnings home.

Homecomings were festive—village doorways had large, red paper characters pasted on them. In the center of every doorway were the characters 福 (fú “good fortune”) or 春 (chūn “springtime”), pasted upside down. When small children see the upside down characters they shout “good fortune is upside down!” or “springtime is upside down!” In Chinese, the word for “upside down” is 倒 dào. This is identical with the pronunciation of the word for “arrived” (到 dào). So the children’s cries of “Good fortune is upside down!” (福倒了 fú dào le) are identical in pronunciation to “Good fortune has arrived” (福到了fú dào le). On either side of village doors are pasted duìlián 对联 or spring couplets, balanced seven character phrases with auspicious messages such as 八方财宝进家门,一年四季行好运 (From all directions wealth enters our door, in all four seasons of the year we have good luck) or 万事如意福临门,一帆顺风吉星到 (All things are as we wish and good fortune is at our door, everything is smooth sailing and our lucky star has arrived).

The Chinese language is rich with opportunities for wordplay, and this richness is most apparent during the New Year in rural China. In Yunnan and Guizhou families eat glutinous rice flour cakes on the eve of the New Year. The sweet, tasty cakes are called niángāo 年糕, whose pronunciation sounds like nián nián gāo 年年高 which means “every year is better than the last one.” Every family will eat fish on the lunar New Year’s eve, saying “every year we have fish” (nián nián yŏu yŭ 年年有鱼) which sounds just like nián nián yŏu yú 年年有余 meaning “every year we have abundance” (Su Laoshi’s second grade class shouted this to me in the hallway on their way to recess Tuesday morning). In the north of China people eat dumplings or jiăozi 饺子 on New Year’s Eve, not only because they are delicious, but because they also illustrate yet another clever play on words. Historically in China, each day was divided into twelve separate two-hour periods or watches. The period from 11.00pm to 1.00am was called 子时 or zĭ shí. On New Year’s Eve as midnight approached the time changed to zĭ shí. The term jiăozi 饺子 or dumpling has a similar pronunciation with jiāozĭ 交子 which means that time has entered the two hour period of zĭ shí—when the day changes from New Year’s Eve to New Year’s Day.

I always felt very fortunate to be able to spend the New Year with families who reunited in their villages—I learned a great deal about cultural traditions including language and food. This New Year, enjoy it with your children, whose teachers have shared with them many of the rich traditions of the Lunar New Year in China. As you enjoy dinner on New Year’s Eve, ask them to teach you about the traditions they have learned in school. You’ll be surprised and delighted by how much they know.

Happy New Year everybody!

Best,

Jeff Bissell

February 2, 2011